On 20 April 1813 Emily Crespigny Hindes was baptised in the church of St Mary-le-Tower at Ipswich, Suffolk.

The name of Emily’s mother was given as Emily Hindes. The infant Emily’s second baptismal name was recorded as ‘Crespigny’, an allusion, it appears, to Charles Fox Crespigny (1785 – 1875), my 4th great grandfather. She was probably his illegitimate daughter and my half fourth great aunt.

Only a month before, on 20 March 1813, Charles Fox Crespigny had married Eliza Julia Trent (1797-1855) in London. The sequence of these events and their proximity is hard to interpret, but it appears that Crespigny was willing to acknowledge Emily Hindes as his daughter, for seventeen years later, on 14 July 1830, he stood surety for a bond on Emily’s behalf, underwriting her passage to Bengal in the so-called ‘fishing fleet’ of Englishwomen seeking a promising young man in the marriage market of the British Raj. Accompanying her was Mrs Eliza Blundell (c. 1807 – 1833), wife of George Snow Blundell, an officer in the army of the East India Company. Eliza Blundell acted as her guardian and chaperone. Eliza’s fare was probably also paid by Charles Crespigny.

The bond was issued in the names of Chas F Crespigny and Philip C Toker, a lawyer of Doctor’s Commons. Philip Champion Toker (1802 – 1882) was Charles Fox Crespigny’s nephew, daughter of his half-sister Clarissa (1776 – 1836) who had married Edward Toker.

“Our Ball” from “Curry & rice,” on forty plates; or, The ingredients of social life at “our station” in India by Captain George Francklin Atkinson (1822 – 1859)

On 1 December 1832 Emily Hindes married George Petre Wymer, a Major of the Honourable East India Company, at Neemuch, east of Udiapur, in Madya Pradesh. Their marriage certificate was witnessed by George Snow Blundell, Captain in the Fifty-first Regiment of Native Infantry.

Marriage record G P Wymer and Emily Crespigny Hindes married Neemuch 1832. Image retrieved from FindMyPast

The fishing expedition had been a success. Emily acquired a husband who,though twenty-five years older than herself, showed considerable promise as an army officer, and indeed, he rose to the rank of general and was knighted for his military service with the Order of the Bath. George Wymer, for his part, got a young wife who gave him five children. Four were born in India; the first two, a daughter and a son named George Crespigny Wymer, both died there in infancy.

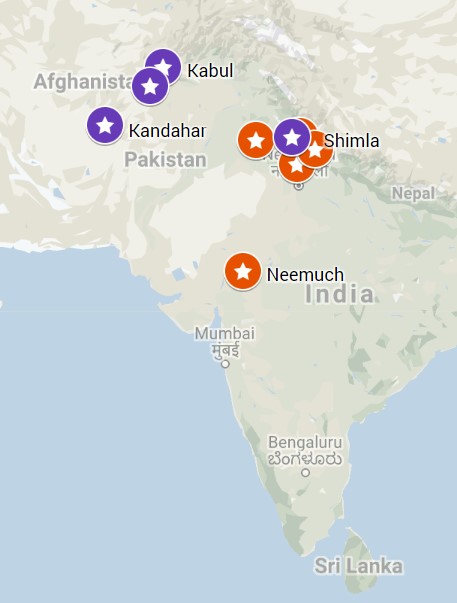

Places associated with the Wymyer family. Red stars indicate where Emily married at Neemuch and gave birth to her children at Kurnaul 1835 and 1836, Ferozepore 1839, and Mussoorie 1843. Her infant son George died at Simla in 1837. The purple stars indicate some of George Wymer’s military activities.

Overgrown with grasses, ferns and lichen, the grave of their son George Crespigny Wymer at Simla is described by Rudyard Kipling in “Out of Society”, an essay first published in the Civil and Military Gazette of 14 August 1886.

Simla from the Kalka Road photographed in the 1910s and published in Kipling’s India 1915

The road around Jakko Hill Simla from Kiplings India 1915. Jakko Road overlooks the little English cemetery described by Kipling several times in poems, stories and essays.

Returning to England about 1850, the family lived on the Isle of Wight and in London. There Sir George Wymer died in 1868, with obituaries in the Gentleman’s Magazine, the Morning Post, the Illustrated London News and elsewhere. These obituaries note that Sir George’s wife was the daughter of C F Champion Crespigny.

Obituary for General Wymer from the Illustrated London News, Saturday, Aug 29, 1868, page 211

The General’s Medals – a rare early Indian Campaign Group of five to General Sir George Petre Wymer KCB comprising Order of the Bath, KCB (Military) Knight Commanders Star (neck and breast badge), Army of Indin 1799-1826 with Nepaul clasp (Lieut G.P.Wymer, 3rd NI), Cabdahar Ghuznee Cabul 1842 and Order of the Dooranee Empire (central enamel missing) and two additional gold suspension bars. The medals were sold by Gorringes in 2013.

After her husband’s death Emily describes herself in the census returns as born in France. Given that she was baptised in Ipswich, Suffolk, this is most unlikely. She was possibly seeking to explain her unusual middle name or, perhaps deliberately, perhaps not, seeking to associate herself with her half-siblings who were in fact born in France.

In the census of 1861 an Emily Hindes, aged sixty-six, is listed as living alone in Aldeburgh High Street, Suffolk, maintained by “Annuity Property.” Born about 1795, this woman would have been of age to bear a child in 1812. It seems likely that she was Emily mother of Charles Fox Crespigny’s daughter Emily and that Charles had supported her thereafter. She died in 1870 aged 75 and was buried at the Anglican Church of St Peter and St Paul, Aldeburgh.

The Fishing Fleet

From 1600, when the East India Company was incorporated by royal charter, foreign travel to and within India was controlled by the Company. British citizens who wished to travel there were required to have the authority of the Company and, in general, this was given only to its employees. Soldiers of the Company were excepted. Other travellers were required to sign a covenant of good behaviour. To enforce the terms of the covenant, guarantors were required. These (there were usually two) were required to issue bonds undertaking to pay a certain sum of money in the event that the person guaranteed broke the terms of the covenant.

In the late seventeenth century the East India Company paid for the passage of women to India in order that Company employees might find British brides to marry. From the nineteenth century women paid their own way but still travelled to India in search of husbands employed by the Company or in the British Army.

A popular account of the Raj white marriage-market is ‘The fishing fleet: husband-hunting in the Raj‘ by the journalist and biographer Anne de Courcy (Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2012.)

de Courcy claims that ‘the bond became an affidavit of the girl’s social standing and, by extension, behaviour: if her parents could afford its cost, they were likely to be of a class that made their daughter a suitable bride for a high-up Company official’. The force of de Courcy’s claim is considerably weakened, however, by the fact that the the bond was imposed on all travellers to India, not just young ladies prospecting for a husband. The Company’s position of political and military dominance in India was extremely fragile, as the events of 1857 were to show. It had strong reasons for excluding troublemakers and riff-raff off all kinds, and the bond, was only incidentally a means of screening out sub-par sheilas. It was really a mechanism for protecting the security of British India.

The East India Company Act 1813 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which renewed the charter issued to the British East India Company, and continued the Company’s rule in India. From 1813 until the passage of the Government of India Act 1833 missionaries, tradesmen and women who wished to travel to India were required to provide bonds.

The wording of the bond was standard. The surety was £200 (at least £17,590 in present day value or $Au33,000). The surety was in addition to the fare.

The Families in British India Society have an index of 12,500 Bonds taken out by many ladies, cadets, ministers of religion and traders between 1814 and 1865. I don’t know if the bond actually had to be paid, if the bonds were paid, how and when were the bonds were redeemed? At, say, $AUS20,000 a pop, this comes to $AUS250 million. The interest on this would have been a nice little earner for the Company.

The bond allowed passage on an ‘Indiaman’ and ensured that the traveller would not be a charge on the East India Company.

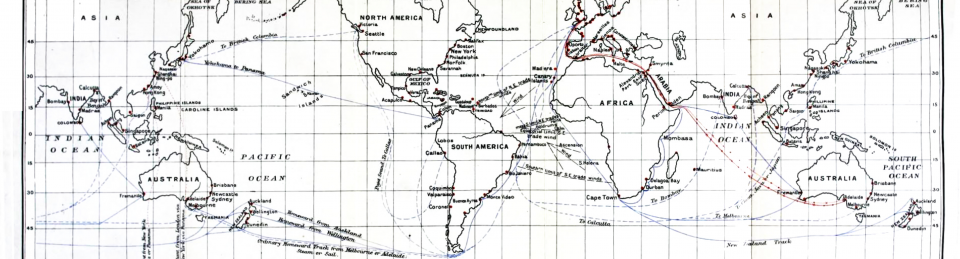

East Indiamen “Madagascar”, circa 1837 In the collection of the National Maritime Museum

Anne de Courcy writes that in the nineteenth century “India was seen as a marriage market for girls neither pretty nor rich enough to make at home what was known as ‘a good match’, [… ] indeed, perhaps not to make one at all.” As the illegitimate daughter, even of a wealthy man, Emily Hindes would seem to fall in the category or women unlikely to make a good marriage in England.

Given the 1830 bond for Emily’s passage to India it seems my 4th great grandfather accepted and took responsibility for his illegitimate daughter and sought to ensure she had a good marriage.

Sources

- The website ghgraham.org/georgepetrewymer1788.html has an account of George and Emily Wymer and their children, with extracts from censuses, obituaries and the probate of wills.

- De Courcy, Anne The fishing fleet : husband-hunting in the Raj (Large print ed). Windsor, Bath, 2013. Pages 4 – 5

- Bonds, Covenants, Indentures and Obligations, Etc. – FIBIwiki, Families in British India Society, 2018, wiki.fibis.org/w/Bonds,_Covenants,_Indentures_and_Obligations,_etc.

- FIBIS database results including:

- Miscellaneous Bonds 1814-1865 Entry from Transcription of Miscellaneous Bonds Number of Bond 7769 Authority of Court 13 Jul 1830 Full Names Mrs. Eliza Blundell and Miss Emily Hindes Description Passengers Presidency Bengal Description of Instrument Bond Date 14 Jul 1830 Sureties Chas. F. Crespigny, Aldburgh, Suffolk, Esquire. Philip C. Toker, Doctors Commons, Esquire. IOR Reference Z/O/1/10 Source Name Miscellaneous Bonds, Nos. 5739-7915 1827-1830

- Ancestry.com and FindMyPast databases

- England, select births and christenings

- India, select marriages 1792 – 1948

- English censuses 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891

- Kipling, Rudyard. “Out of Society.” The New Readers’ Guide to the Works of Rudyard Kipling, Kipling Society, www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/rg_sketches_31.htm. First publication: Civil and Military Gazette, 14 August 1886

At least he did support mother and daughter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

CONGRATULATIONS! Your blog has been included in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2019/11/friday-fossicking-29th-nov-2019.html

Thank you, Chris

LikeLike

Pingback: F is for Ferozepore | Anne's Family History

Pingback: P is for palanquin | Anne's Family History